“Ego clouds and disrupts everything: the planning process, the ability to take good advice, and the ability to accept constructive criticism. It can even stifle someone’s sense of self-preservation. Often, the most difficult ego to deal with is your own.”

Extreme Ownership, former Navy SEAL commander Jocko Willink

I am really fortunate to be involved in the construction of big structures. Working on bridges or major structures can be likened to playing in the NHL or MLB: You’ve made it through the minor leagues, survived the long bus rides, the roadside motels, eating at diners and playing games in front of a few dozen fans. You’re gotten the call from the “big club.” You never thought you’d make it when you first started out. And once you’ve made it, you never want to go back down.

I liken that analogy to what happens to some of us in the construction industry. Working on bridges & big structures provides a challenge like none other. Sure, it might not be for everyone. But if you’re like me and thrive on working in an environment where you need to bring your A-game to work every day, where you are constantly challenging your knowledge base & your problem solving skills, I can’t think of another sect of the construction industry that is better-suited for the challenge.

Being “drafted into the majors,” however, brings with it a significant amount of expectations: Are you at the top of your game? Have you spent enough time in the minor leagues forging your talents? Can you function at a high level? Do you have the mental fortitude to stay in the game 24/7/365? Are you good-to-go?

One of the themes of my writings is presenting post mortems of things that have gone bad. Learning from mistakes. We learn from failing. If we don’t, then we’ve failed to learn.

I opened this post with the quote from Jocko Willink, a former Navy SEAL, who has written an outstanding book titled Extreme Ownership. The quote speaks to me on so many levels: Ego truly is the enemy. Acknowledging that we screwed up and need to make things right is, well, part of being a man of character. It means that you have the ability to put your ego aside and deal with issue free of emotion, or fear, or worrying about how you are perceived. Do you have the ability to separate your ego from the situation?

Mistakes don’t happen a lot in our industry. Really. Our industry is built on the backs of thousands of professionals, contractors and workers who pride themselves on doing things right 100% of the time. I have only met a handful of individuals in our industry who don’t strive for perfection in everything they do, and those individuals are few, and they usually don’t last long. Most of us are perfectionists. We want things right ALL the time.

So, dealing with mistakes – and I’m talking about BIG mistakes here – is a pretty rare occurrence. And unfortunately, when the big errors do arise, there are usually negative consequences that need to be dealt with. The remedies often have a financial impact. They are physically repairable. They can damage a reputation. Sometimes, they even effect people’s lives….

So, putting ego aside is a basic necessity to get through this post. I lived through a mistake on a recent bridge project. Others lived through it too. Nobody was hurt. Egos may have been bruised. But at the end of the day, the problem got solved.

Building a Railroad Bridge

In January of 2013, I got a call from Kevin, our company’s president. I was going to be re-deployed. Arsenal Road, the project I had been working on since 2010, was still far from being completed. But out of the blue, I found out that I would be going someplace else….

The new project involved building a railroad bridge for Canadian Pacific in Bensenville, Illinois, on the southwest corner of O’Hare Airport. Construction of a new 2-track railroad bridge, combined with the reconstruction of the adjacent Irving Park Road & York Road intersection, would provide congestion relief to a high-volume location that, for decades, was a source of traffic backups for its users. The existing Canadian Pacific at-grade crossing saw as many 25 trains come through the intersection daily, making for mile-long traffic backups when slow-moving trains were operating.

On paper, the job was to take 2-1/2 years.

When you are given orders, you deploy, whether you like it or not.

Onto a new journey I went.

Getting the Job Rolling

2013 was a year to get the railroad approach embankments and the bridge foundations started. Construction went pretty smoothly despite utility relocation interferences. Problems came and went. We pushed through them. That’s what we do.

Abutment construction started in the summer of 2013 with no major issues. The construction process is pretty simple: Dig a hole for the abutment footing. Drive the piles. Install the rebar. Frame & cast concrete. Walla – 2 bridge abutments. All in a day’s work.

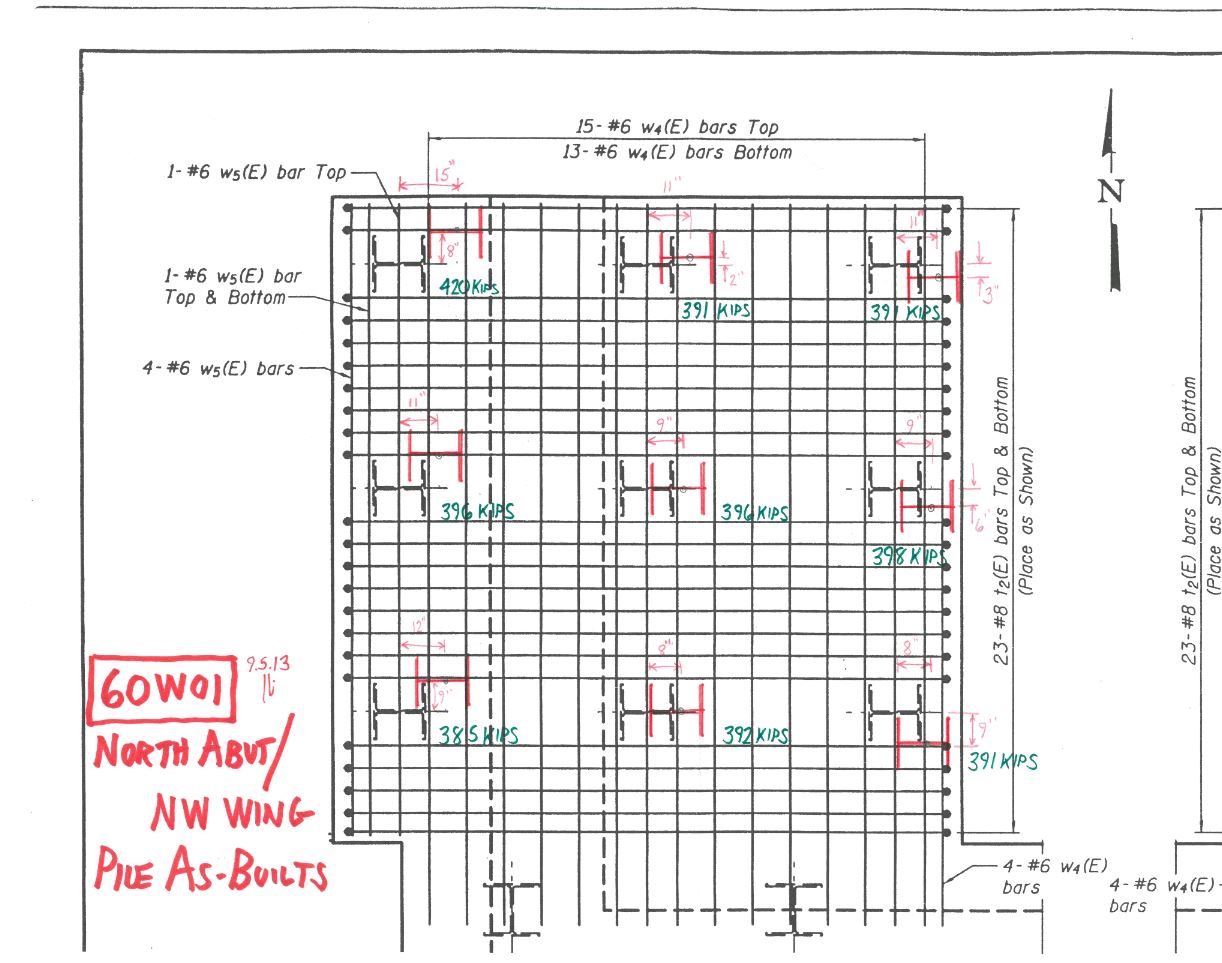

So one morning, after some of the north abutment piling had been driven, I got some as-built information from our survey crew: They had checked the locations of the northwest wingwall piling and determined that piling wasn’t driven in the proper locations.

Just to give you some perspective, this is a picture of the corner of the abutment just prior to casting the concrete footing:

I plotted the surveyors’ information: Sure enough – There was a shift in all of the piling in the cluster. The shift didn’t seem like an inordinate amount off, but, it was enough where we would need to adjust the abutment footing forms. IDOT specifies that piling be installed to a maximum dimensional tolerance of 6″ from the design location. So, all of the piles were out of tolerance, but, not so much that caused hair to start falling out of my head.

So, I put together a clean as-built of the locations (the actual sketch is below). I wasn’t sure if the design guys would need it, but I included the actual driven pile capacity of each of the piles, just in case the guys needed to run any calculation relative to loading, overturn resistance or eccentricity issues that might be born from the missed locations.

I didn’t know it at the time, but adding the pile capacity on the sketch would be the first step in turning our worlds upside-down….

Let’s Talk About Pile Resistance

So I sent the sketch to the Springfield Bridge Office. I got an email back from Dewey, our contact down there: His report was that he wanted to have the design engineer check the loadings on the piles as-driven to see if there was any change to how the piles were being loaded at their current locations.

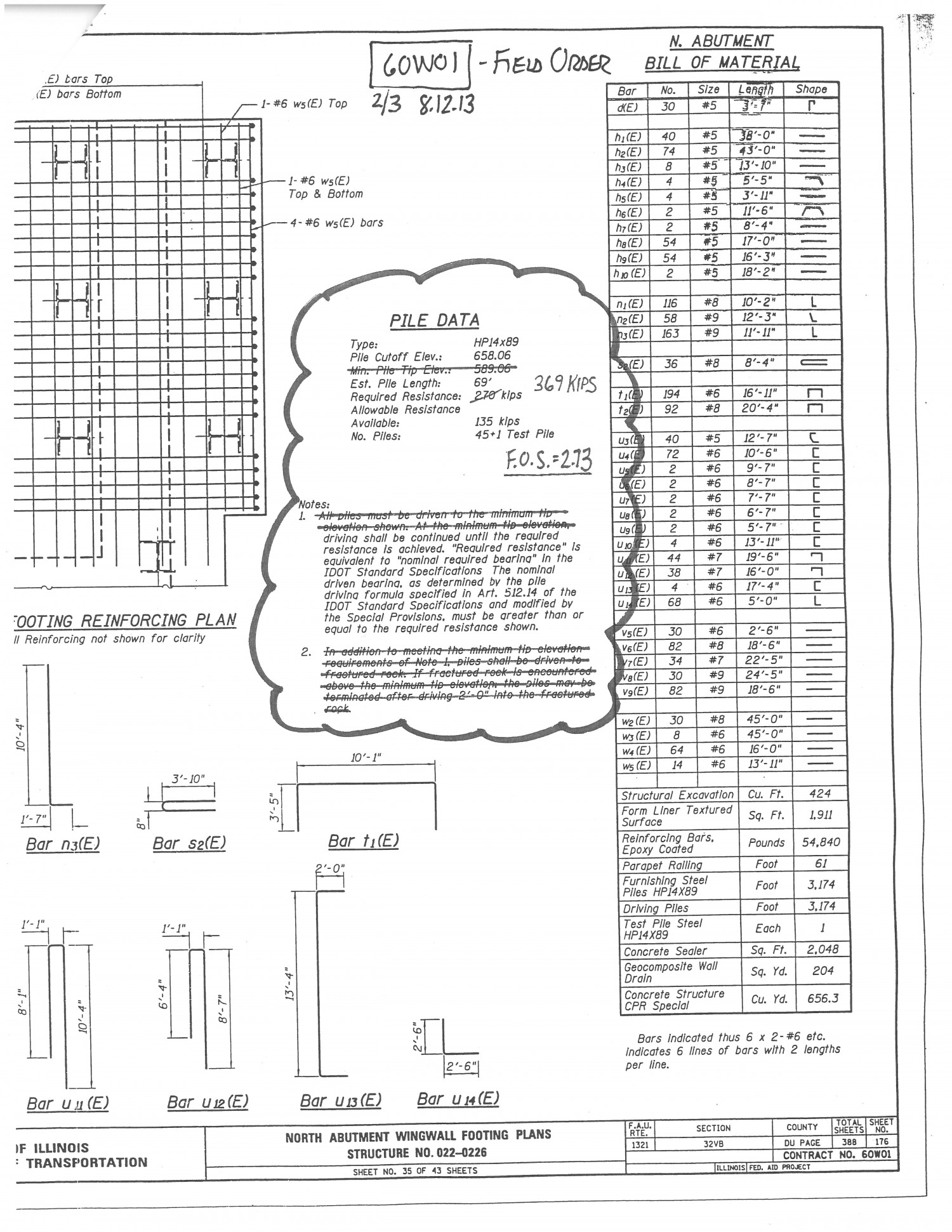

Now, these piles were originally designed to have a capacity of 270 kips. That’s a pretty light-duty pile capacity for a major structure, but, that’s what the drawings specified. Earlier in the summer, we’d ask the designers a question regarding the minimum tip that the piles needed to be driven to. And at that time, the designers noticed that they hadn’t incorporated the necessary Factor of Safety into the pile capacities as they presented them on the drawings. We needed to increase the required capacity to 369 kips. Whoa – Good thing we knew that before we installed them, right? I guess that validated our initial concern about the 270 kips seeming to be light. We issued the information to the Contractor as a drawing modification (shown below).

Now, if you look at the wingwall piling as-built, from a bearing perspective, our piles were in good shape since they all exceeded 369 kips. We would subsequently need to adjust the footing form locations so as to encapsulate all of the piles. Not a big problem.

A couple of days after we sent the as-built to the bridge office, I got a call from the designer: He wanted to know if we’d, in fact, driven the piles to 369 kips. I told him yes, we had, because that’s what the plans called out for as the “Required Resistance.” It was then that he told me that there were some issues with the bearing capacities. He told me that his engineers were telling him that the pile capacity was actually supposed to be a derivative of the “Required Resistance” and that the pile capacity for the north abutment was supposed to be higher than the 369 kips we had driven them to….

Holy Shyt. The piles are under capacity.

The Gut Check

As soon as I hung up the phone, I grabbed the drawings. I grabbed the specifications. I grabbed our pile charts, and pile hammer data and our driving logs. Is what the Designer was calling “Required Resistance” on their drawings the same as “Nominal Driven Bearing” as it is called for in the IDOT Specs? The note on the drawing says it is. Was there some sort of factor that we are supposed to be applying? When the pile capacity changed from 270 kips to 369 kips and we issued the field order to the Contractor, did I / we miss something?

Holy Shyt.

As vivid as the screen that I’m typing on is today, I remember sitting in our field office feeling pale as a ghost. Dave, our field engineer who had covered the pile driving, and Dennis, my boss & our company’s construction chief, were both there. When I told them about my conversation with the designer, we all had the same look on our faces: We’ve got the entire north abutment driven out, the rebar is all tied, the footing is completely framed, and the Contractor is scheduled to pour day after tomorrow. And now, the designer is telling us that the pile capacities are too low.

I started digging. Digging into the numbers. Digging into our pile tables. Digging into the test pile data and our production pile logs. Check. Check. Check. Everything we checked was good. What are we missing?

Now I’m starting to get dizzy. I’ve been driving piles for years. I’ve been with pile crews, counting blows, using pile charts, calculating hammer energies the old fashioned way. I’m not seeing it. Dennis is in his 70’s: He’s driven more piles in his lifetime than I ever will, and he’s not seeing it. I’m trying to figure out: Did we do something wrong?

The dust eventually settled. And we came to find out the answer – No, we didn’t do anything wrong.

The next day, I start seeing emails coming in from the designer, from IDOT, from the Bridge Office, from the Foundation’s unit in Springfield, everyone focusing on the issue. And as the facts started to come out, the problem reared its head: The designer’s pile capacities, even with the initial adjustment from 270 kips to 369 kips were not calculated correctly. Our abutments were currently under-designed. We would need to get the problem corrected.

That day, Danny, our IDOT RE, put the Contractor on notice: A Stop Work Order was given to them, shutting down all activities on the bridge abutments until a solution was devised.

Initial Post-Mortem

So, now that we have a diagnosis, let’s step back from the emotional whirlwind for a second and look at a couple of things.

First, you’ve just lived through a day in the life of a Resident Engineer.

While the motoring public likes to drive past our worksites and see the guys in the white hard hats “just standing around,” it is FAR from the truth. While the labor forces are actively working with their hands and machines, we are working too, it’s just that our work is done between our ears, not necessarily with our hands. Our efforts are rarely seen….

When trouble hits, we have to be able to react. And in this case, Holy Jesus, I reacted: I swear, I almost shyt myself. I like to think that I can keep a pretty stoic manner about me when embroiled in problem-solving, but I know on that afternoon in our field office, I sure let my guard down….

Problems happen. In construction, it’s inevitable. But we’re talking little problems. This piling issue: This is classified as a BIG problem. And while the initial goal is always to solve the problem first and foremost, there’s a little word that always is sitting in the back of your head when you are in responsible charge of something…..

Liability.

We can’t avoid it. It’s part of life in this day & age. It’s unfortunate. I wish I lived in an earlier time, when a man’s handshake and his word were binding. You did right by someone because you gave them your word. You would do whatever you had to do to uphold your word. If you made a mistake, you simply made it right. And you didn’t have to worry about getting sued because you made a mistake, you just fixed it.

Well, I still live my life in that manner. The trouble is that today, much of society doesn’t.

Nobody wants to be the guy who has to call his boss and say “Hey Chief, I screwed up.” And as this issue unfolded, unfortunately, somebody would have to make that call.

Believe me: There’s no gloating when you see an error start to unravel. There’s no joy in dealing with a mistake. There’s no “fun” in seeing industry associates having to raise their hands and say “It was my fault: I made a mistake.” Karma is a bitch. I don’t want it to be my turn next…..

So here’s the thing: What was grinding at my core when we were looking into our checks & balances was simply this – Why was the terminology listed in the “Pile Data” table on the drawings so, well, non-standard? Typically, IDOT-generated plans ALWAYS call the pile’s specified bearing to be the “Nominal Driven Bearing.”

Why did our plans have to list it as “Required Resistance?” Why did they have to add Note 1 where it says “Required Resistance” is equivalent to “nominal required bearing”…?” Maybe this was something Canadian Pacific wanted on the drawings? There was certainly a good reason, we just didn’t know what it was. And looking back, it was the source of my angst: We applied the bearing criteria as we read it, but when the designer called and questioned it, my natural reaction was to wonder what was wrong.

When all the dust settled and it was confirmed that we did, indeed, drive the piles correctly, you could have felt my sigh of relief 100 miles away…

Next Time

In my next post, we’ll take a look at the steps that were taken to solve the problem. We’ll discuss some pile driving basics, and finally we’ll dive into my After Actions Review and hopefully learn a few lessons from this situation.

Yeah, kinda like a recurring nightmare. Why does it seem like the piling waters are always a little murky…..